Decentralized Grocery Marketplace on ONDC

Enabling Local Retailers Through Open Commerce Infrastructure

Business Context

India’s Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) was introduced to decentralize e-commerce by enabling local retailers to participate in digital marketplaces without relying on dominant platforms.

Unlike traditional grocery apps (e.g., BigBasket, Blinkit):

Pricing is not controlled by the platform

Inventory is managed by individual stores

Delivery may be store-managed or third-party

Platform has limited operational control

The opportunity:

Build a grocery marketplace that enables local stores to sell digitally while maintaining consumer trust in a decentralized ecosystem.

1.1 Business Objectives

Enable ONDC-integrated local grocery stores to sell via mobile app

Provide a consistent buying experience despite decentralized control

Support multi-store discovery and ordering

Handle store-led or third-party delivery options

Drive adoption among both retailers and consumers

This was not a traditional e-commerce build — it was a platform design problem under infrastructure constraints.

My Role

I led

Experience architecture for the consumer-side app

Marketplace trust design

Product discovery and listing structure

Multi-store cart logic

Delivery partner selection experience

Checkout and payment flow

Cross-functional alignment with ONDC integration teams

The Core Marketplace Challenge

Traditional grocery platforms control:

Pricing

Inventory

Promotions

Delivery SLAs

Refund policies

ONDC-based commerce removes that control.

This created three fundamental UX challenges:

Trust without centralized control

Clarity across multiple fulfillment models

Preventing platform blame for store-level issues

The design problem became:

How do we create reliability in an unreliable ecosystem?

3.1 Market & User Insights

Before structuring the marketplace experience, we analyzed grocery shopping behavior and existing platform expectations.

Key findings from survey and market analysis:

38% of users value time savings above all else

30% prioritize the ability to place large, consolidated deliveries

Security, contactless delivery, and cashless payment remain strong drivers

BigBasket and Blinkit dominate usage, setting expectations around speed and reliability

Unlike centralized grocery platforms, ONDC does not guarantee:

Standardized pricing

Delivery speed consistency

Inventory synchronization

Unified return/refund handling

This created a structural tension: Users expect platform-level reliability, but the infrastructure distributes responsibility across stores and delivery providers.

Therefore, the design strategy focused on:

Making fulfillment responsibility explicit

Reinforcing store identity throughout the journey

Surfacing delivery timelines early

Ensuring price and charge transparency at every step

This research reframed the problem from "building a grocery app" to designing a trust-first decentralized marketplace experience.

3.2 ONDC Channel App Landscape

Before defining our marketplace architecture, we analyzed existing ONDC buyer applications operating under the same infrastructure constraints, including:

Mystore

eSamudaay

SellerApp

ITCstore.in

These platforms faced identical structural realities:

Store-controlled pricing

Decentralized inventory

Variable delivery ownership

Limited centralized accountability

Observed Experience Patterns

Across these ONDC channel apps, we identified:

Inconsistent visibility of store identity

Limited clarity on who fulfills the order

Complex or layered navigation structures

Weak distinction between platform vs store responsibility

Insufficient price and charge transparency at checkout

Most apps prioritized network enablement but underinvested in consumer trust architecture.

Strategic Gap Identified

The ONDC ecosystem demonstrated infrastructure readiness — but lacked experience maturity.

Users entering these apps still carried expectations shaped by centralized commerce platforms. The gap was not feature-related; it was clarity-related.

Design Implication

We differentiated not by simplifying the system artificially, but by making its complexity legible.

This informed several structural decisions:

Persistent elevation of store identity

Explicit delivery partner selection

Store-grouped cart architecture

Transparent checkout breakdown

Reinforced fulfillment accountability

This analysis ensured our solution was ecosystem-aware rather than interface-deep.

Marketplace Architecture Decisions

4.1 Store-Centric Transparency

Since prices were set by store owners, we made store identity explicit throughout the journey:

Store name visible in listing

Ratings displayed prominently

Delivery time clearly shown

“Free delivery” vs paid delivery explicitly separated

This reframed responsibility.

Users understood they were buying from a specific store — not from the platform itself.

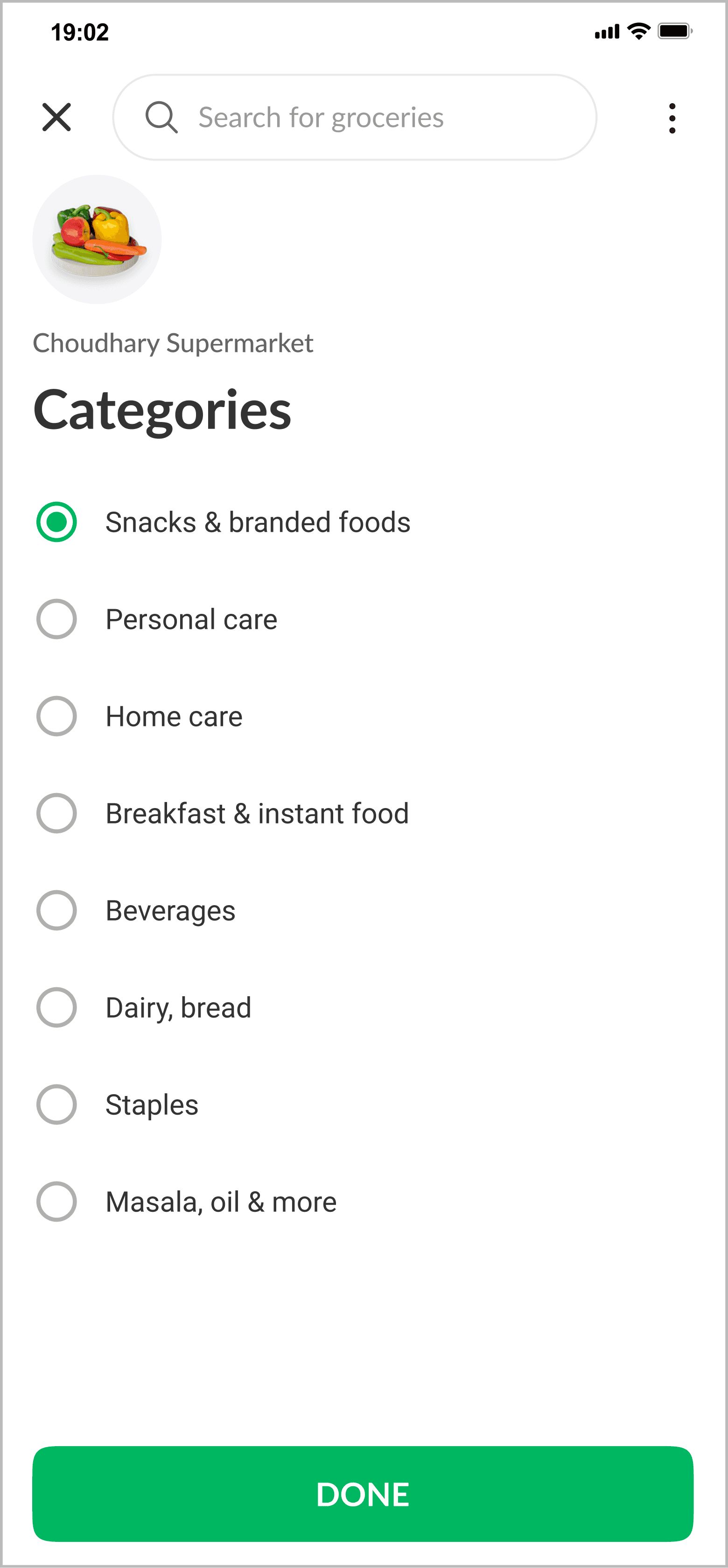

4.2 Multi-Store Product Discovery

In category view:

Store metadata displayed with each product

Delivery time surfaced early

Filters accessible and contextual

Category selection layered by store context

This reduced confusion in decentralized listings.

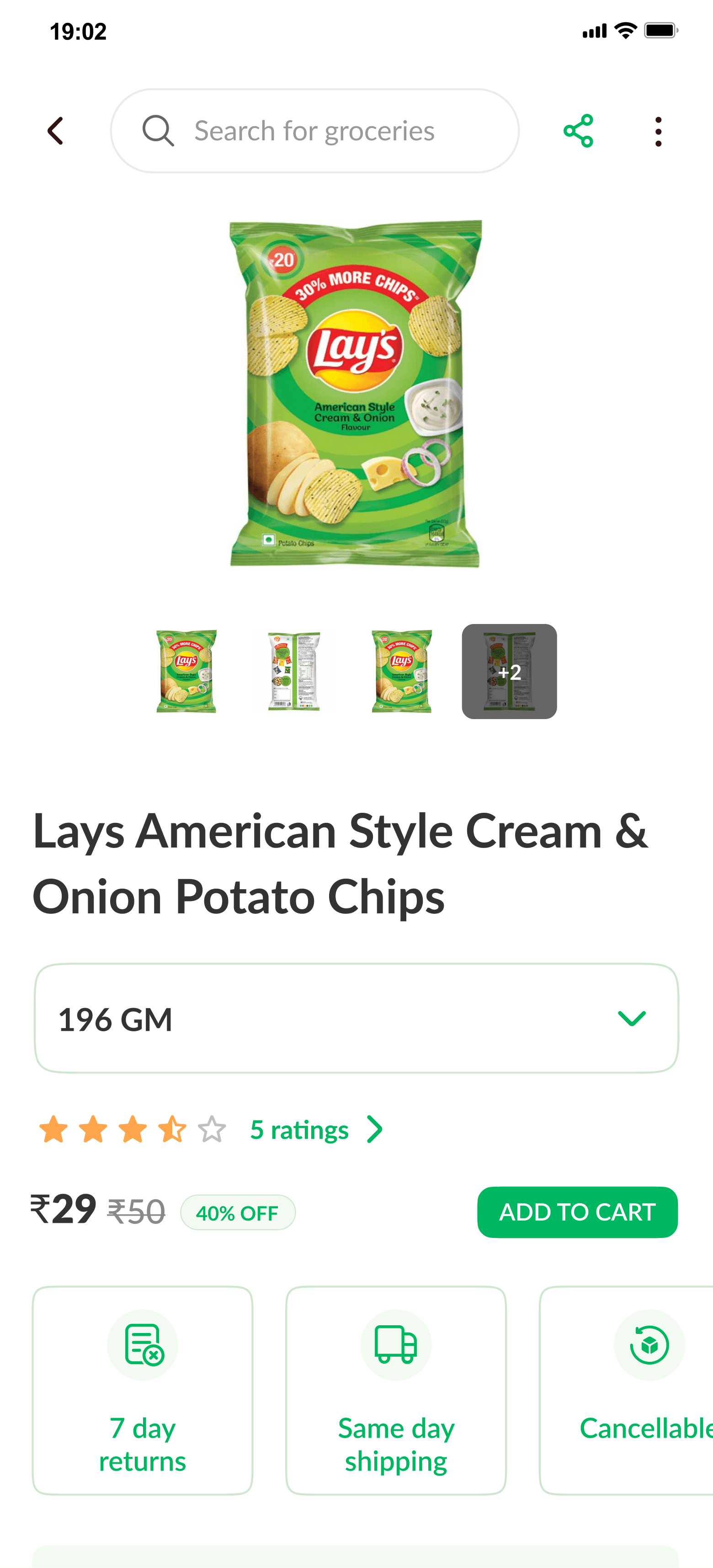

4.3 Variant & Inventory Handling

Variant selection (e.g., 196g, 420g, etc.) was designed as a separate step:

Explicit “Select Variant” modal

Clear price display per variant

Discount badge consistency

This reduced mismatch between store-managed inventory and consumer expectations.

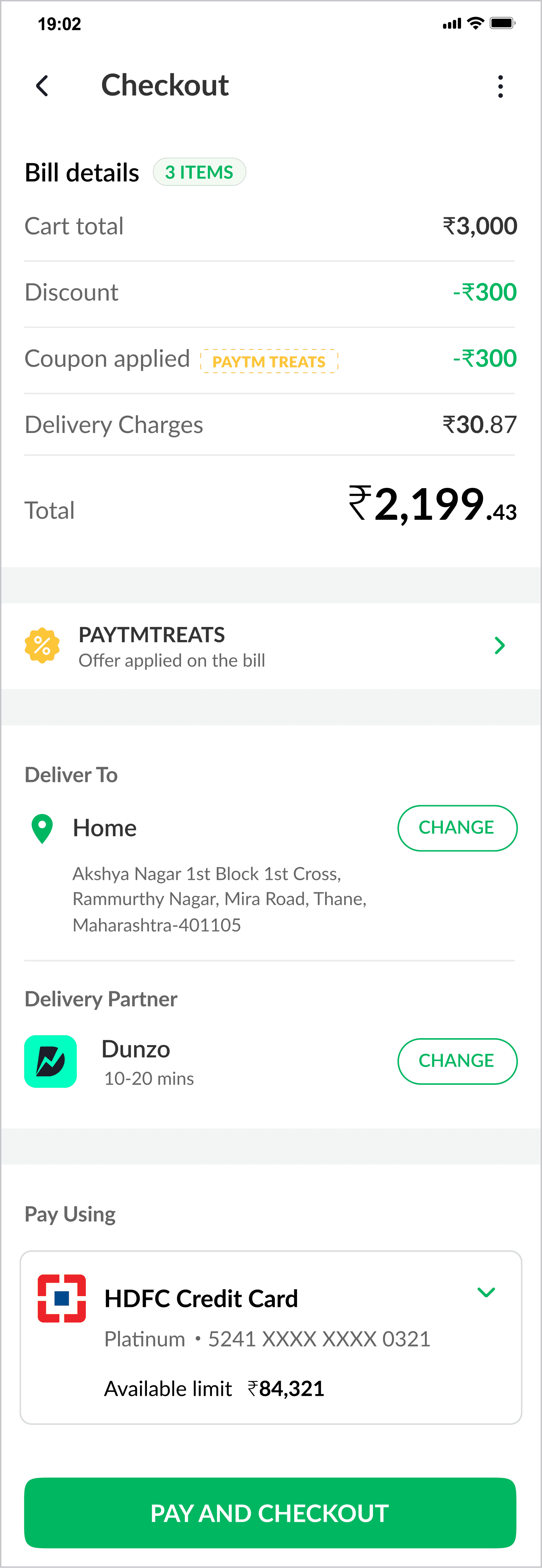

Delivery Architecture

5.1 Dual Fulfillment Model

Users could choose:

Store-provided delivery (often free)

Third-party logistics providers (e.g., Dunzo, LoadShare)

We intentionally exposed delivery partner selection instead of auto-assigning.

Why?

ONDC does not guarantee fulfillment consistency

Store-led delivery may have different reliability

Pricing may vary

Transparency reduces friction

5.2 Delivery Partner Selection

Displayed:

Delivery time estimates

Ratings

Delivery charges

Promotional incentives

This shifted delivery from hidden backend logic to visible user choice.

It also reduced ambiguity in case of delivery failure.

Cart & Multi-Store Complexity

6.1 Store-Grouped Cart

Cart items were grouped by store:

Store header visible

Subtotal per store

Quantity controls per item

Clear separation of items

This supported:

Multi-store purchases

Store-specific delivery fees

Clear accountability

Without grouping, users might assume single-vendor responsibility.

6.2 Address & Delivery Context

Address confirmation was persistent and changeable within cart.

Delivery partner displayed again at checkout.

Redundancy was intentional — it reinforced clarity before payment.

Checkout Under Decentralized Control

Checkout had to handle:

Store pricing (variable)

Coupon application

Delivery charges (store or partner dependent)

Payment selection

7.1 Bill Transparency

Breakdown included:

Cart total

Discounts

Coupon applied

Delivery charges

Final payable amount

Clear monetary breakdown was critical in decentralized pricing.

7.2 Payment Selection

Standard payment options were supported (e.g., credit card).

Given the complexity of upstream marketplace actors, payment clarity was emphasized.

Usability Validation & Structural Testing

8.1 Objective

Before finalizing the experience, we validated whether users correctly understood the decentralized marketplace structure. The goal was not visual refinement, but architectural comprehension.

We specifically tested whether users understood:

Multi-store cart grouping

Store-level responsibility

Delivery partner selection logic

Price breakdown transparency

Variant and inventory clarity

8.2 Method

Task-based usability testing using realistic grocery scenarios

Participants familiar with centralized grocery apps

Scenario included multi-store cart building and delivery comparison

Observed structural misunderstandings rather than UI preferences

8.3 Key Findings

Users initially assumed platform-level accountability.

→

Reinforced store identity at listing, cart, and checkout.

Users preferred to see the cheapest delivery option first, then the fastest.

→

Reordered delivery partner presentation accordingly.

Users compared prices across stores when searching for specific products.

→

Increased prominence of store metadata in listings.

Users built carts over multiple sessions before completing checkout.

→

Ensured cart persistence and clear subtotal grouping per store.

Hiding out-of-stock variants caused frustration.

→

Displayed unavailable variants visibly instead of removing them.

8.4 Architectural Impact

Validation led to deliberate structural refinements:

Increased repetition of store identity

Explicit delivery partner selection

Stronger price breakdown hierarchy

Clear accountability reinforcement across touchpoint

This reduced user confusion in a system where control was inherently distributed.

Post-Order Feedback

The “Order is on the way” persistent banner:

Reinforced order confirmation

Displayed order ID

Reduced post-purchase anxiety

In decentralized commerce, reassurance is essential.

Key UX Challenges & Trade-Offs

10.1 We Did Not Control Pricing

Solution:

Emphasized store identity

Displayed discounts explicitly

Surfaced price per variant clearly

10.2 We Did Not Control Delivery SLAs

Solution:

Made delivery partner selection explicit

Displayed delivery times and ratings

Allowed users to choose trade-offs

10.3 We Did Not Control Inventory Accuracy

Solution:

Explicit variant selection

Clear product-level metadata

Store-context reinforcement

Systems-Level Thinking

This project required designing for:

Consumers

Store owners

Delivery providers

Government-backed open network infrastructure

It was less about optimizing a funnel and more about designing:

Governance clarity

Trust signals

Accountability architecture

Expectation management

Impact

Successful ONDC integration

Multi-store order support

Operationalized store-led + third-party delivery model

Reduced confusion in decentralized purchasing

Most importantly:

It translated an open commerce protocol into a coherent consumer experience.

Key Takeaway

Designing in a decentralized ecosystem shifts the role of UX from interface optimization to trust architecture.

When control is distributed, clarity becomes the product.